Why is Mutchmor Road so wide?

Exploring how misguided transportation plans haunt Ottawa for generations

In my op-ed for the Ottawa Citizen earlier this month, I said the City of Ottawa’s new Transportation Master Plan was filled with zombies, fairies, and dragons. These were bad proposals that never die, planned projects that had magic powers to drive transit-oriented development just by being a line on a map, and the looming costs and congestion of continued automobile-oriented transportation planning.

For today’s newsletter post, I’m going to extend the fantasy metaphor even further by profiling how the ghosts of past transportation plans can continue to haunt our roads for decades. Spooky!

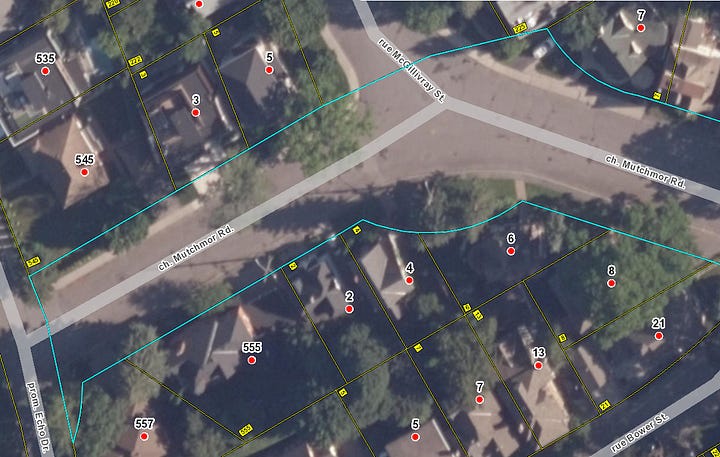

Mutchmor Road is a local street that stretches four blocks in the quiet neighbourhood of Old Ottawa East. It has a lot in common with other tree-lined residential streets in the area—but two things stand out that make Mutchmor unique: it diagonally cuts across the standard grid, and it is incredibly, bizarrely wide.

Unlike most neighbourhood streets that have a typical width of around 8.5 meters (enough for two-way traffic and on-street parking), Mutchmor is nearly twice as wide: 15.25 meters of pavement curb-to-curb (50 feet), with a 24 meter (80 feet) right-of-way. That’s more appropriate for a four-lane arterial or collector, not a local residential street.

There’s enough unused pavement on Mutchmor to solve Ottawa’s pickleball court shortage.1 So why is Mutchmor so wide? I’ve been curious about this question for a long time, and I’m glad to have finally found the answer buried in Ottawa’s transportation plans from over a hundred years ago. Let’s start the story back then.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the City of Ottawa was in the midst of a planning boom. The growing and expanding city was trying to clean itself up after multiple typhoid epidemics and beautify itself to suit its new role as capital. This meant that there were all sorts of plans being created to improve the livability and stateliness of Ottawa through transportation and housing initiatives. Some of these plans were made by experts hauled in from abroad—but there was also a local, self-taught planner named Noulan Cauchon who would play a large role in how the City of Ottawa was shaped between the wars.

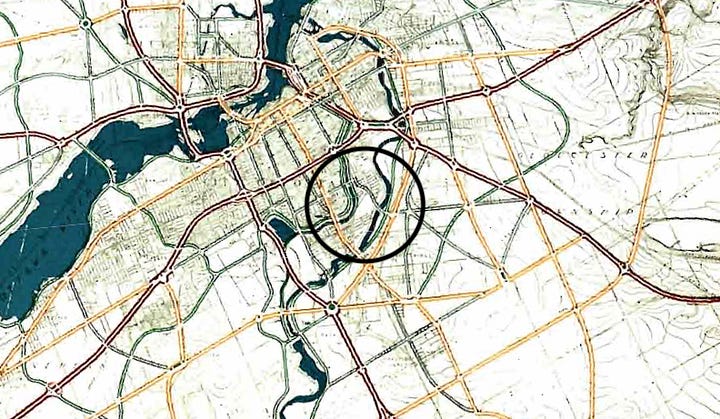

Cauchon was an avant-garde planner and an idiosyncratic person. Aside from his planning career, he’s also known for being the first male citizen in Ottawa to wear shorts—quite scandalous at the time. Cauchon produced an enormous amount of mostly unbuilt schemes for transforming Ottawa—some more outlandish than others—with many showing his fascination with diagonal streets. One plan from 1912 showed downtown crisscrossed with diagonals, which would have made Canada’s capital look much more like Washington, D.C.—if only all those pesky buildings weren’t in the way.

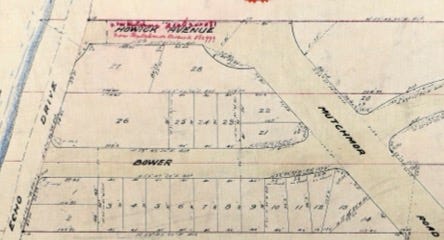

As the first Town Planning Commissioner for the City of Ottawa in the 1920s, Cauchon’s work often involved the more plodding work of rounding street corners. But this role also allowed him to occasionally flex his creativity through influencing the design of new streets when large lots were being subdivided. When this opportunity presented itself in Old Ottawa East (then just Ottawa East), Cauchon didn’t hesitate to throw in a diagonal: Mutchmor Road. As Cauchon wrote at the time, his plan for Mutchmor “constitutes a further recognition of the virtue of diagonals in a city plan.” (Another diagonal created by Cauchon at this time was Sherwood Drive.)

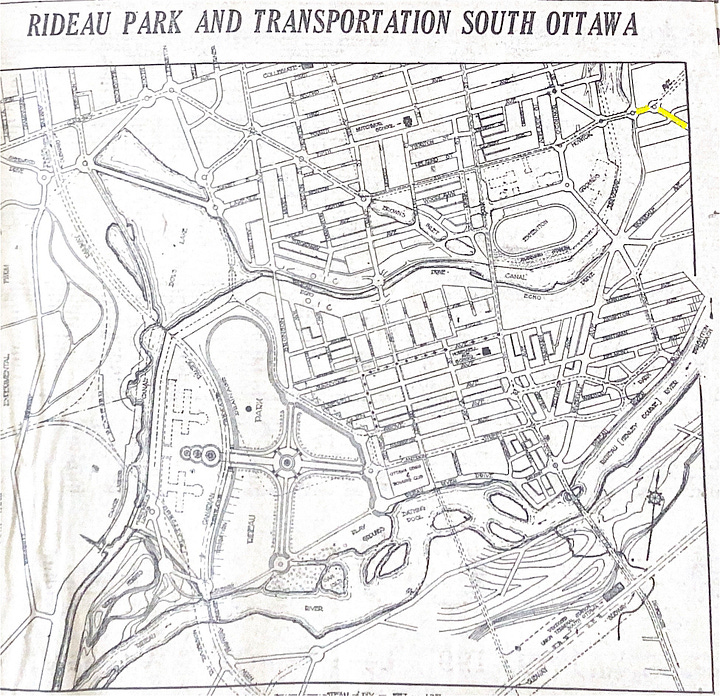

To understand why Cauchon felt so strongly about including Mutchmor, you have to look at his wider plans for the City. One of his designs from 1923 (below) shows that Cauchon didn’t view Mutchmor in isolation, but part of a network of diagonals and traffic circles. Here, Mutchmor (then Howick Avenue) would have a double traffic circle at McGillivray and Echo before crossing the Rideau Canal with a new bridge, cutting through Lansdowne Park, continuing west on Holmwood (known as Centre Street), then connecting with Carling Avenue with another diagonal from Percy Street that would then link with the diagonal Sherwood. In this case, Mutchmor would obviously not be a local residential street, but a load-bearing cross-town arterial.

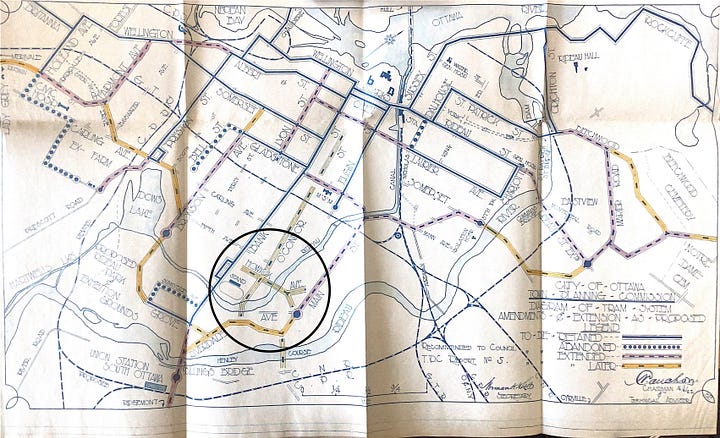

Another Cauchon design from that period shows a new streetcar line using Mutchmor (Howick) to connect Lansdowne Park with Main Street. Crosstown motor traffic and a streetcar line would naturally need a wide street. But the bridge across the Canal was not built in Cauchon’s time, nor was a new streetcar line added here. Mutchmor Road was not even extended to intersect with Main Street until 1943, eight years after Cauchon died.2

Mutchmor didn’t then—and doesn’t now—have traffic circles at McGillivray Street and Echo Drive. Instead, the three-pronged intersection at McGillivray and Mutchmor is an uncontrolled, blank slab of pavement: no stop signs, yield signs, or even paint. But if you look at the original plan of subdivision from 1922, you can see that the lot lines at the intersections were curved so as to prepare for traffic circles in the future. In fact, these lot lines remain that way today.

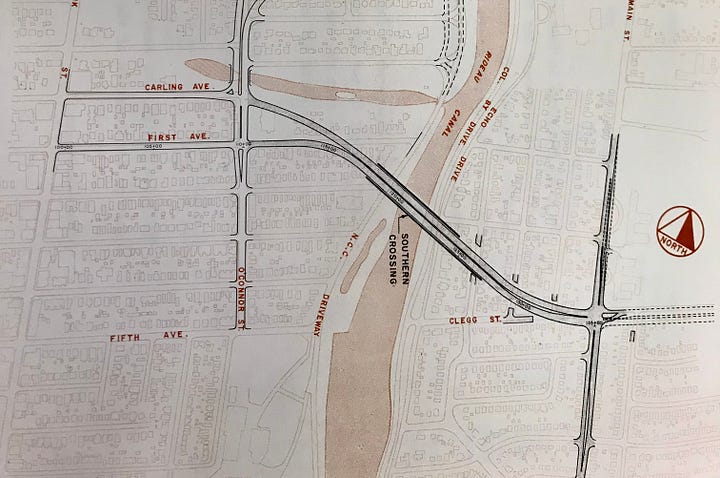

The idea of using Mutchmor as a crosstown route was revived in the early 1950s with the release of the infamous Plan for the National Capital by Jacques Gréber. The Gréber Plan called for a new arterial road connecting Main Street and the Glebe via Mutchmor Road and a new bridge over the Rideau Canal. This was not built. A subsequent plan in the 1960s instead diverted the proposed canal crossing further north, which would require demolishing dozens of homes to widen Clegg Street to six lanes and join it with First Avenue and Glebe Avenue (then Carling Avenue). This also did not happen. Eventually, crosstown traffic was designed to follow the four-lane arterial of Main Street over a rebuilt and widened Pretoria Bridge.

You may know how that story ends. It turns out Main didn’t need so many lanes, and it was narrowed in the 2010s from four lanes to two. The excess pavement was reconfigured into wider sidewalks, raised cycletracks, and landscaping. Hawthorne Avenue—which connects Main to Pretoria Bridge—is in the middle of a reconstruction that will narrow it too. And while a link over the canal was finally built between Old Ottawa East and the Glebe at Fifth Avenue and Clegg Street in 2019, the Flora Footbridge only allows pedestrians and cyclists. In other words, it is possible to redesign streets for sustainable transportation even if they were originally intended for high-volume car traffic.

So let’s go back to the original question: Why is Mutchmor Road so wide? The simple answer is that a hundred years ago, an eccentric town planner with a thing for diagonal streets thought Mutchmor would be the spine of a new crosstown route—and, despite those plans evaporating and heavy car traffic never materializing in the area, nothing has been done in the century since to change it.

Should it be changed? Absolutely! Wide streets encourage fast driving—dangerous for everyone, especially pedestrians and cyclists. Huge expanses of pavement contribute to urban heat islands, driving up the local temperature. And wide streets aren't exactly pretty either. If you took the current 15.25 meter roadway and narrowed it to the standard 8.5 meters, you’d have 6.75 meters of space (3.375 on each side) for wider sidewalks, gardens, and trees. The narrower street and enhanced public realm would make for a far safer and more pleasant environment. The rebuilt street could even have a small, landscaped roundabout at McGillivray Street—though not the multi-lane traffic circle envisioned by Cauchon.

But there’s no reason to expect any changes happening soon. Refurbishing anachronisms like Mutchmor simply aren’t a priority for the municipal government. Streets like this only get rebuilt if the pipes underneath it needs replacing, and Mutchmor isn’t on the list of upcoming projects (though, for what it’s worth, some of the grates appear to be originals).

Until the time those pipes need to go, Mutchmor Road will remain just an abnormally wide curiosity—an asphalt ghost that serves as a reminder that bad transportation plans, even if unrealistic and unfinished, can haunt cities for generations.

Unfortunately, the City of Ottawa’s new Transportation Master Plan calls for $2.7 billion on new or widened roads in the next 20 years. Other than neglecting more important investments that could use a few billion dollars, this car-focused transportation approach has two possible outcomes, both bad: either these projects induce extra demand for driving, or we’re going to end up with many more Mutchmors in the years to come.

According to my rough calculations, there’s about 12 pickleball court’s worth of excess pavement (1,000 square meters) on the 250 meter long street. More practically, with some space in between them, an enterprising individual could paint about eight pickleball courts in the middle of the street without impeding traffic.

This one-block section between Mason Terrace and Main Street was subsequently narrowed to 8.5 meters in the early 1970s.